How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia

📝 usncan Note: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia

Disclaimer: This content has been prepared based on currently trending topics to increase your awareness.

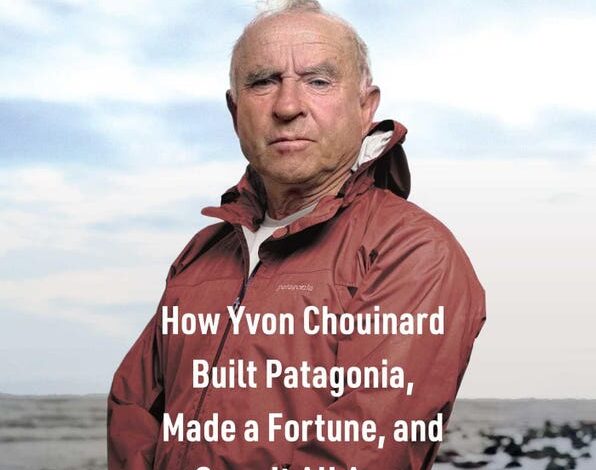

Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chounaird Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away

Simon & Schuster

In a business world obsessed with growth at any cost, Yvon Chouinard stands as perhaps the most unlikely billionaire in corporate history. The founder of Patagonia, who gave away his company to fight climate change and famously declared “Earth is now our only shareholder,” embodies a series of contradictions that defy conventional business wisdom.

New York Times journalist David Gelles spent years following Chouinard around the world—from the Snake River in Wyoming to the peaks of Patagonia itself—to understand how a rock climber became a reluctant capitalist and built one of the most admired companies on earth. His new book, “Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away,” reveals a CEO who defied every conventional business wisdom and somehow succeeded anyway.

I recently sat down with Gelles to discuss the book and the paradoxes that define both Chouinard and his company. You can watch the entire interview here.

The Anti-Jack Welch

Gelles previously chronicled Jack Welch, the legendary GE CEO who Fortune magazine crowned “manager of the century.” Where Welch pursued relentless growth and shareholder value maximization, Chouinard deliberately restrained Patagonia’s expansion. Where Welch embraced the spotlight, Chouinard shunned attention. Where Welch optimized for quarterly earnings, Chouinard killed his own bestselling product because it was harming the environment.

“These couldn’t be two more different CEOs,” Gelles explains. Yet both shared an obsession with quality—they just defined it in radically different ways.

For Welch, quality meant efficiency and market dominance. For Chouinard, quality evolved into something far more complex: products that worked flawlessly, lasted decades, were made without toxic materials, produced in factories that treated workers well, and created by companies that were good corporate citizens.

The Piton Decision That Changed Everything

The defining moment in Patagonia’s history came in the early 1960s, when Chouinard made a decision that would horrify every McKinsey consultant. His company’s main product—pitons, the metal spikes climbers hammered into rock faces—was literally destroying the granite walls of Yosemite. These 10,000-year-old formations were getting pockmarked by an increasing number of climbers using his gear.

So Chouinard stopped selling them.

“Pitons were basically everything he sold,” Gelles notes. “When he made the decision to switch to chocks and hexes, that was essentially turning his back on his one key product.”

The move to “clean climbing” gear that could be removed without leaving a trace jeopardized his entire business. No consultant would have recommended it. But it established a pattern that would define Patagonia for decades: choosing environmental responsibility over short-term profits, even when it threatened the company’s survival.

Black Wednesday and the Soul of Business

Success brought new challenges. By the late 1980s, Patagonia was experiencing explosive 40% annual growth. The company hired aggressively, scaled up operations, and planned for continued expansion. Then the economy crashed.

“Black Wednesday” forced Patagonia’s first mass layoffs in company history. Hundreds of employees lost their jobs. The company flirted with bankruptcy. The experience scarred Chouinard so deeply that it fundamentally changed how he thought about business.

The crisis led to two permanent changes: Patagonia would always maintain substantial cash reserves (like Steve Jobs did with Apple after his own brush with bankruptcy), and the company would deliberately restrain growth to avoid another round of devastating layoffs.

But Black Wednesday also sparked deeper soul-searching. Chouinard took his team to Patagonia—the actual place in Chile and Argentina—for conversations about what it really meant to be in business. They weren’t just selling clothes; they were trying to protect the environment and show other businesses there was a different way to operate.

Strange Bedfellows: Patagonia Meets Walmart

Perhaps no relationship better illustrates Patagonia’s contradictions than its unlikely partnership with Walmart. Through a consultant named Jim Ellison, the hippie outdoor gear company found itself working with the Arkansas retail giant on sustainability initiatives.

Chouinard actually flew to Bentonville to speak with Walmart employees. Walmart executives traveled to Ventura to study Patagonia’s operations. The companies even considered making a product together (which, Gelles notes, would probably be worth a fortune on eBay today).

The partnership ultimately failed when Walmart’s sustainability-minded CEO departed and his replacement lost interest. But for Chouinard, the experience reinforced his belief that public companies, beholden to quarterly earnings, are “hopeless” when it comes to meaningful environmental action.

The Unresolvable Paradox

What makes Chouinard fascinating—and maddening—is his ability to hold contradictory positions simultaneously. Gelles identifies the core tension: “Chouinard wanted his workers to be happy, but he was also hard charging. He wanted to be generous, but he also wanted to stay in control. He wanted Patagonia to be lean, but also abundant. He wanted the company to be profitable, but also charitable.”

This paradox extends to Patagonia’s fundamental business model. The company runs marketing campaigns telling people to buy less stuff—”Don’t Buy This Jacket” was a famous 2015 ad—while simultaneously needing customers to buy new Patagonia gear to survive.

“How do you square that circle?” Gelles asks. “Well, you don’t. And that’s okay. That’s actually the story.”

The $3 Billion Giveaway

The contradictions reached their ultimate expression in 2022, when Chouinard gave away his $3 billion company rather than sell it or go public. The Forbes billionaire list had always infuriated him—being listed in 2017 was “one of the worst days of his life.”

Working with Warren Buffett’s banker Byron Trott, Chouinard’s team devised an unprecedented structure. They placed 2% of voting shares in a purpose trust that ensures Patagonia remains independent and mission-driven. The remaining 98% went to the Holdfast Collective, a 501(c)(4) that receives all profits not reinvested in the business and distributes them for environmental causes.

The structure accomplished Chouinard’s contradictory goals: preserving the company’s independence, removing his family’s billionaire status, avoiding a foundation with their name on it, and maximizing money for environmental activism. They even chose a 501(c)(4) over a 501(c)(3) to preserve the ability to engage in political advocacy, despite the less favorable tax treatment.

Business for Good in Crisis

Chouinard’s approach feels especially relevant as the “business for good” movement faces growing skepticism. The same CEOs who condemned President Trump’s actions in his first term now sit at his table during his second. The Business Roundtable’s 2019 statement redefining corporate purpose beyond shareholder value is rarely mentioned today.

“The critics are justified to be skeptical,” Gelles admits. But he argues against drawing overly black-and-white conclusions. While political winds have shifted, corporate America has made genuine progress on employee well-being, sustainability, and supply chain management.

Patagonia remains one of the few companies still “unabashedly saying what they think” on controversial issues. CEO Ryan Gellert regularly criticizes the current administration’s environmental policies, while Chouinard himself, now 86, prefers to spend his time fishing and “pays as little attention to the news as he possibly can.”

The Enduring Influence

Perhaps Patagonia’s greatest impact lies in proving that contradictions don’t have to be resolved to be productive. The company has influenced corporate practices from childcare (Patagonia offered on-site childcare in the 1970s) to supply chain transparency to employee benefits.

Even failed partnerships like the Walmart collaboration planted seeds. KKR now pays nursing mothers to travel with companions on work trips—the kind of policy that might not exist if Patagonia hadn’t pioneered family-friendly workplace practices decades earlier.

Chouinard never solved the fundamental tension between running a for-profit company and protecting the environment. He just decided that trying to do both—despite the contradictions—was worth the effort. In a business world that demands clean answers and quarterly certainty, maybe that’s the most radical position of all.

The dirtbag who accidentally became a billionaire and then gave it all away reminds us that some paradoxes are meant to be lived with, not solved. In trying to run a responsible company, Chouinard created what Gelles calls “an unsolvable paradox.” But perhaps that’s precisely what makes it solvable—not by finding the answer, but by embracing the tension.

For business leaders seeking a different path, Chouinard’s story offers both inspiration and warning: building a values-driven company is possible, but it requires accepting contradictions that would make most executives deeply uncomfortable. The question isn’t whether you can resolve the paradox between profit and purpose—it’s whether you’re willing to live with it.