The Wild West Of NIL

📝 usncan Note: The Wild West Of NIL

Disclaimer: This content has been prepared based on currently trending topics to increase your awareness.

Warren Zevon once famously sang “send Lawyers, Guns, and Money,” a term that came to represent the merging of political, legal, and financial interests that are brought into a situation to exert influence. Paying college athletes for their athletic performance has been a shadowy pillar of University athletics for decades, until now. After years of defending/defining the concept of amateurism, a Supreme Court decision forced the NCAA to revoke its restrictions on athlete compensation. The floodgates opened on July 1, 2021, when athletes were officially allowed the opportunity to monetize their personal brands via their Name, Image, and Likeness (“NIL”). Transactions that once took place “under the table” were now out in the open. Like all new frontiers, the college athletics landscape brings massive opportunity. Still, the lack of precedent and enforcement procedures can make it feel like The Wild West.

THE ORIGINAL NIL DEAL

Eric Dickerson was born on September 2, 1960 in Sealy, Texas. Widely regarded as one of the best running backs to ever grace the gridiron, Dickerson was a highly recruited prospect out of his small Southeastern Texas town. He ultimately decided on Southern Methodist University “SMU” to continue his football career. After an extensive investigation into SMU regarding improper benefits being offered to prospective recruits, the NCAA handed down one of the harshest penalties in the history of collegiate athletics: forfeiture of their remaining season, reduced scholarships and a probationary period banning them from any televised games and future bowl appearances. Affectionately referred to as “THE DEATH PENALTY,” this decision altered the future of SMU football for decades.

It does make one think, if SMU was offering cash and other perks, maybe there were other universities offering cash, or even farmland and heads of cattle, as a compensation package.

“Everyone was doing it,” including the likes of Reggie Bush Chris Webber Rick Pitino, but SMU was caught first and paid a dear price. Jay Bilas has been one of the most public figures in support of the NIL frontier, advocating for the athletes.

LAWYERS

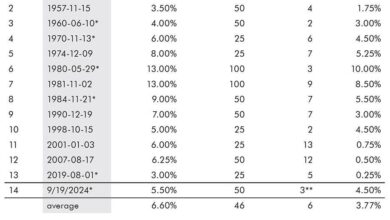

The seismic changes in college sports were not voluntary NCAA implementations. Paying players publicly and not requiring them to sit out one year upon transfer, were forced reactions to major losses in the court room.

The most influential NIL-related lawsuits center on antitrust issues. For those that are not licensed to practice law (like me), antitrust violations occur when companies engage in anticompetitive behavior that harms consumers or the market. Two fundamental NCAA rules that were viewed as “anticompetitive,” along with key lawsuits, ultimately led to what we know as NIL today.

1. Old NCAA Rule #1: Limit athlete compensation to scholarships:

One core argument is that the NCAA conspired with its member conferences and universities to engage in “price fixing” by collectively denying athletes compensation beyond education-related benefits like scholarships, room, and board. Imagine if all the major banks on Wall Street agreed to only pay their interns with free training and lunch, despite the fact their production contributes to multimillion dollar deals. Unlike banking interns, college athletes are the primary reason for multimillion dollar deals.

- O’Bannon v. NCAA (2014): Ed O’Bannon was a UCLA standout and NBA draft pick in 1995. While playing the EA College Basketball videogame, he noticed a player that looked and played just like him. Considering NBA and NFL players were paid for their representation in videogames, O’Bannon felt the NCAA’s restriction of compensation was unfair. So, he filed and won a lawsuit in what was the first major win against the NCAA’s limitation on compensation. But rather than allowing EA to pay players for licensing rights, the NCAA stuck to its restrictions that led to the abrupt end of the EA college videogame franchise.

- NCAA v. Alston (2021): Shawne Alston played running back in 37 games for the West Virginia Mountaineers from 2009-2012. He and a group of NCAA Division I athletes found it unfair that athletes were limited to earning only education-related benefits like those detailed above.

By denying athletes the opportunity to monetize their Name, Image, and Likeness, the NCAA was effectively acting with unfair monopoly power.

Athletes were enabled to make money from corporate sponsorships, high net worth “boosters” and everything in between with no oversight. - House v. NCAA (2024): Collegiate swimmer Grant House represented athletes in a lawsuit arguing that athletes who had missed the chance to profit from their NIL in broadcasting, videogames, and third-party NIL revenue were owed money. With the potential to bankrupt the NCAA if taken to trial, the suit was settled with the NCAA agreeing to pay former college athletes a sum of $2.8 billion over the next ten years. To gain more control over the current NIL frenzy, the settlement also permits universities to directly pay their student athletes a share of revenues annually, starting at $20.5 million. Judge Claudia Wilkens granted final approval in July, just in time for the 2025-2026 academic year.

2. Old NCAA Rule #2: Athletes that transfer must sit out 1 year:

Prior to 2021, college athletes who transferred schools would have to sit out one season before being eligible to play. Facing mounting antitrust scrutiny (see: Alston – again), the NCAA decided to get ahead of it and permit athletes one free transfer that allowed them to compete immediately. Even though this limitation is intended to ensure academic stability, it can still be viewed as anti-competitive for athletes seeking better situations.

- State of Ohio et al. v. NCAA (2024): A coalition of states challenged the NCAA’s remaining restrictions on transfers, arguing that the adjusted rule still imposed unreasonable restraint on athletes. Newfound transfer freedom allowed athletes to seek the best fit.

GUNS

If you read my prior article: Athletes, Entertainers, & The Fight For Relevance you will remember that athletes have a short window in life to profit off their talents and every second of on-field production matters. Prior to the Alston 2021 ruling, athletes who were seeking a transfer to another program were required to sit out one year of competition (barring a few exceptions). The real gun fight now takes place in the transfer portal.

As a result of the transfer process changes, the portal has become much more active with a higher level of competition and an increased focus from schools to win now opposed to developing talent over four years. The portal also creates a bottleneck for high school seniors who now must wait their turn to get a shot at playing time and could force them to make a pit stop at a junior college “JUCO”. With this major shift, it is interesting to get the point of view from a player that isn’t in the spotlight but watching the new landscape develop around him.

Outside of diehard Ohio State fans, most college football enthusiasts do not know of NOLAN BAUDO.

Nolan Baudo is a 5’10, 180LB, 2023 preferred walk-on wide receiver at THE Ohio State University hailing from Marist High School on the Southwest Side of Chicago.

Nolan has learned/befriended some of the most elite talent in the country—players like Carnell Tate, Marvin Harrison Jr., Emeka Egbuka, Jaxon Smith-Njigba, and Jeremiah Smith. These aren’t just teammates; they’re friends and current/future NFL stars. Not to mention 47% of the National Championship team answered: “Baudo” when asked who they would most likely hangout with. Baudo has gained insight into a critical shift happening across college football.

In Baudo’s eyes, NIL has created a noticeable divide between average, good, and great players. He sees a pattern: average players are often preoccupied with the paycheck, good players are similarly focused on compensation over performance, but the great players—those destined for the next level—understand that production comes first. For those next level athletes, the money follows the performance, not the other way around. The more they produce in college tends to translate into a higher NFL draft pick which means: more money tomorrow.

Beyond NIL, Baudo emphasizes something even more fundamental: culture and chemistry. With rosters pushing 110 players, he believes alignment is everything. If even a handful of players aren’t fully bought into the program’s vision, the result is friction and instability. “Money will never win a championship,” Baudo often says. “But great culture and unmatched team chemistry can give you a real shot.”

At Ohio State, that culture is built around a single word: fight. It’s a mentality that extends far beyond game day. Whether it’s grinding through winter workouts, battling in the heat of preseason camp, or staring down a fourth-quarter deficit in the playoffs, players are expected to fight—for their team, their goals, and the brotherhood. That mentality isn’t just preached, it’s lived daily.

What stood out to Baudo most during the 2024 season was the team’s chemistry. It wasn’t surface-level camaraderie—it was a deep trust that bound the team together. Players weren’t just teammates, they were family. They hung out together, supported each other, and most importantly, trusted each other implicitly.

But even with NIL, culture, and chemistry in place, Baudo believes the defining factor of a championship team is its players—specifically, its leaders and what he calls “dudes.” In the football world, a “dude” isn’t just a talented player. It’s someone who shows up with purpose, plays with fire, and pushes everyone around him to rise to the same standard. It’s about intentional effort, day in and day out. Not everyone has that in them—and as strength coach Mick Marotti often says, “You either are, or you ain’t.”

Leadership, Baudo explains, is another critical component. At Ohio State, it’s not given—it’s earned. Through grueling workouts, accountability, and mutual respect, leaders emerge. Coach Marotti plays a huge role in that development. His approach forces players out of their comfort zones, constantly stretching their limits. To Baudo, growth only happens when you’re uncomfortable, and real leadership is forged in those moments.

That leadership was never more important than after Ohio State’s loss to Michigan on 11/30/2024 – a moment that could’ve unraveled their season. Instead, the response was defiant. The players held a closed-door meeting, led entirely by the team’s veterans. They hashed everything out, spoke honestly, and ended it arm-in-arm in prayer. From that moment on, it was Ohio State versus the world.

And the result? A national championship.

“That,” Baudo says, “is Ohio State. That is culture. That is chemistry. That is how you win.”

MONEY

Make no mistake about it – college athletics is a big business with billions of dollars at stake, and money is the gasoline that makes the engine go. With the recent House settlement, arranging direct player payment, this engine is as close as it has ever been to professional grade.

When looking to understand how exactly Northwestern can afford to build an $850 million stadium or how the state of Georgia can justify paying a coach $130 million or how a freshman can earn millions before setting foot on campus, you need to start from a 10,000 foot view far above any individual university athletic department.

Let’s start by looking at the crown jewel of college sports: March Madness. In the 2023-2024 fiscal year, the NCAA pulled in over $1.3 billion in revenue, around 90% of which is derived from this iconic tournament. This includes postseason ticket sales and, far more importantly, the sale of media rights. CBS and Turner Sports are set to cough up $1.02 billion for exclusive control over eyeballs in March. And why not? People love watching their brackets break, and advertisers love things that people watch, which makes March Madness media rights as defensible and attractive as any other investment in sports. Which brings us to what hosted the most-watched non-NFL sporting event of 2024-2025: the College Football Playoff (“CFP”).

Due to what has arguably become its consistent lack of foresight, the NCAA lost control of college football in the 1980s, ultimately leading to the independent operation of the CFP. This entity, which now oversees a 12-team playoff, rakes in an estimated $1.3 billion from its media contract every year—significantly more than its basketball counterpart (ouch!). If the NCAA is not getting this football money, who is? That would be the conferences and their university constituents, with the “Power 4” (SEC, Big 10, Big 12, and ACC) dictating the terms of the college football industry.

If you were to view a conference as a person who earns a regular salary, you can view the money received from March Madness and CFP payouts as a sort of performance-based side hustle. The real money (their “salary”, per se) comes from independently negotiated media rights deals with distributors who broadcast regular season conference games and conference championships. The SEC, for example, brings in over $500 million per year from its own deal tied to TV and radio rights. Its exceptional performance in the 2025 NCAA Tournament earned it roughly $70 million in performance-based payouts from the NCAA. Its CFP presence earned another $25 million in payouts, which does not even include its undisclosed base payments.

These numbers illustrate the sheer magnitude of money in the college sports ecosystem. Bear with me here as we tie it all together.

Universities receive payouts from all these sources: the NCAA pays out most of its revenue to its members with conferences doing the same. On top of this, universities can profit from the sale of their other multimedia rights, including things like sponsorships, merchandise, advertising and more. Wealthy alumni also provide a healthy revenue stream for athletic departments through donations. Schools use this money to fund stadium renovations, pay coaches, and subsidize money-losing sports.

Prior to 2021, the money beyond scholarships, room and board ended there (in the pockets of the Universities). None of that money mentioned was flowing “legally” to the athletes that put in the work to sell tickets and TV viewership.

Well, at least not at the surface. As alluded to previously, many athletes accepted under-the-table payments from schools (and their partners) who knew their contributions have a meaningful impact on their (and their partners’) bottom line. Even after the courts acknowledged that these athletes were owed their fair share, the NCAA compliant schools had no way to pay it. So, collectives filled that role.

These collectives are essentially school-associated fundraising units that redirected the flow of donor money from the institutions to the athletes.

And while they also served as a middleman in legitimate NIL deals between companies and athletes, they were mainly a front for boosters to throw cash at football and basketball rosters. Schools will directly pay their players millions of dollars.

The money is real. And now, for the first time in the history of college sports, it is in the open for all to see.

While that sounds like a semi-satisfying resolution, the conversation around athlete compensation is not even close to over. The concepts sound clean, but the legal, financial, and logistical mess of education-oriented institutions having to function like professional for-profit sports franchises is just now beginning to reveal itself.

Very few university athletic departments are profitable, with football and men’s basketball as the primary revenue generators that outnumber their cost to the University.

Questions about the sustainability of the business model start to arise.

Where will they get the money to pay students? Will the well run dry of wealthy donors who have plowed millions of dollars into the post-Alston college athletics landscape? How inventive will universities and conferences have to be in generating new revenues? On-field sponsorships? Jersey patches? Private equity?

At least one thing is certain: Money TALKS and the NCAA was forced to LISTEN.

Nicholas C. LoMaglio is a registered representative with UBS Financial Services, since 2008, and authors thought leadership articles for Forbes on the business of athletics.